- Our Schedule

- Join The Fun!

- Our Activities

- Tiny Tigers (Ages 4+)

- Taekwondo (Pre-/Teens)

- Yongmudo (Teens/Adults)

- Self-Defense

ACTIVITIES OVERVIEW

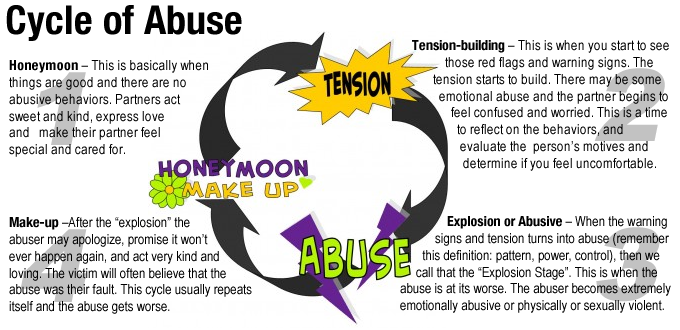

Teen Dating Violence (TDV) is a pattern of abusive behaviors that someone uses for power and control over a girlfriend or boyfriend. Because this behavior is not about support and respect, it only gets worse over time. And, it creates an increasingly more dangerous situation for the young victim.

The Centers for Disease Control defines TDV “as the physical, sexual, psychological, or emotional aggression within a dating relationship, including stalking. It can occur in person or electronically and might occur between a current or former dating partner.”

A 2017 study by the National Institute of Justice found that 69% of youth ages 12 to 18 who were either in a relationship or had been in the past year reported being a victim of teen dating violence.

Additionally, 63 percent of that same sample acknowledged perpetrating violence in a relationship.

Psychological abuse was the most common type of abuse victimization reported (over 60 percent), but there were also substantial rates of sexual abuse (18 percent) and physical abuse victimization (18 percent).

Percent of U.S. high school students (grades 9-12) that report experiencing some form of Teen Dating Violence in the year prior to the survey.

8.5%

Physical TDV

9.7%

Sexual TDV

19%

Any TDV

(Physical, Sexual, or both)

29%

LGBTQ+ Students

GET HELP!

If you or someone you care about is in an abusive relationship, call the National Dating Abuse Hotline at 1-866-331-9474.

Go to: Get Help...Right Now

Dating violence can occur in person, online (Facebook, Instagram, and other social media), or through technology (on the phone, via text messaging, email). The Centers for Disease Control defines four different forms of teen dating violence:

Psychological/Emotional. Verbal or non-verbal communication with the intent to harm a partner mentally or emotionally and exert control over a partner. Non-physical damaging behaviors like insults, threats, screaming, constant monitoring, or isolation.

Physical. Any intentional use of physical touch to cause fear, pain, injury, or assert control over a partner by hitting, kicking, shoving, strangling, or any other type of physical force.

Sexual. Forcing or attempting to force a partner to take part in a sex act and/or sexual touching when the partner does not consent or is unalbe to consent or refuses to take part. It also includes non-physical sexual behaviors like posting or sharing sexual pictures of a partner without their consent or sexting someone without their consent.

Stalking. A pattern of repeated, unwanted attention and conact by a current or former partner that causes fear or safety concern for an individual victim or someone close to the victim. Includes being watched, followed, monitored, or harassed. Can occur online or in-person, and include giving unwanted gifts.

Other forms of dating or relationship violence are defined for adults:

Digital. Using technology to bully, stalk, threaten, or intimidate a partner using texting, social media, apps, tracking, etc.

Financial. Exerting power and control over a partner through their finances such as taking or hiding money or preventing a partner from earning money.

It’s not good: Several studies show a strong connection between dating violence experienced during adolescence leading to behavioral and health problems as young adults for both boys and girls with girls being more likely to suffer long-term negative effects including experiencing victimization in adult relationships (Mulford; Exner-Cortens).

Teens that experience abuse in their adolescent relationships as either victim or victimizer (or both), show emotional and temperamental instability for life with long-term physical ill-health and disturbed mental state. “Approximately 1 in 5 women and nearly 1 in 7 men who were victims of rape, physical violence, and/or stalking by a partner, first experienced some kind of dating violence between the ages of 11 and 17 years.” (National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, 2010 Summary Report; CDC).

Adverse health outcomes include:

Girls that are victims of teen dating violence can exhibit increased antisocial behavior, depression, binge alcohol drinking habits, cigarette smoking, marijuana use, and suicide attempts.

Boys that experience violence in a dating relationship can develop increased antisocial behavior, depression, smoking, thoughts of suicide, and drinking more alcohol. (Mulford; Exner-Cortens; Taquette)

TDV in adolesence associated with future dating and interpersonal violence in adulthood.

High risk behaviors and poor mental health outcomes — including depression and anxiety — particularly for TDV victimization.

It is unclear of the association between TDV and suicide attampts. Studies are limited due to no health records and reliance on self-reporting. (Piolanti)

“Prevention programs have demonstrated efficacy in reducing teen dating violence.” (Taquette, 2019)

The following diagram, also known as the Violence Continuum, shows the pattern of unhealthy relationships. Although it’s normal for people in a healthy relationship to disagree, how those disagreements are resolved is a huge difference between healthy and unhealthy relationships. Note that the longer an unhealthy relationship continues, the darker and more frequent the explosions or “storms” in an unhealthy/abusive relationship become.

These Are The 10 Most Common Warning Signs Of An Abusive Relationship according to JenniferAnn.org:

Threatens others regularly.

Serious drug or alcohol use.

History of violent behavior.

Blames you for his/her anger.

History of discipline problems.

Insults you or calls you names.

Trouble controlling feelings like anger.

Tells you what to wear, what to do or how to act.

Threatens or intimidates you in order to get their way.

Prevents you from spending time with friends or family.

Research studies have shown that the behavior of adolescents can be affected by various media including movies, television, music lyrics, music videos, video games, magazines, and social media.

Although a causality of media use on behavior cannot be confirmed, associations between media use and attitudes and behavior are demonstrated in a number of studies. For example, associations between mass media use with adolescent issues such as body image and obesity have been found. Additional studies have documented associations of media use with various adolescent risk behaviors including tobacco use, alcohol use, substance abuse, aggression, violence, and sexual activity. (Manganello, 2008; O’Hara, 2012)

Music and television, for example, have received decades-long criticism for excessive violence, sex, and other behaviors (example sources?). Beginning in 1954, the U.S. Government began holding inquiries into the effects of violence portrayed on television upon children. (Anderson et al., 2003)

Likewise, movies have received criticism for depictions of certain behaviors.

Media also has the potential to influence teen dating violence attitudes, knowledge, and behavior. In other words, adoloescents can learn dating behaviors — positive and negative — from what they read, hear, and watch through mass media. One study found watching music videos made women more accepting of [BEHAVVIOR]. [SOURCE]

Concern about depictions of violence in mass media and the potentially harmful effect on youth has been of interest for over 70 years. (Anderson et al., 2003)

[MORE DETAIL]

Examples of Relationships

Examples of notable depictions of unhealthy relationship dynamics in cinema include:

Gone With The Wind

GWTW was a best-selling book published in 1936 by Margaret Mitchell depicting plantation life in the Southern states before, during and after the U.S. Civil War. It was made into a blockbuster movie in 1939 starring Clark Gable and Vivian Leigh winning 10 Academy Awards including Best Actress, Best Director for Victor Fleming, and Best Picture. Hattie McDaniel won for Best Supporting Actress becoming the first Black American to be nominated for and winning an Oscar. GWTW is #6 on the American Film Institute’s List of the 100 Greatest American Films of All Time and remains the highest grossing film of all time when adjusted for ticket price inflation.

[INTRODUCE CRITICISMS GOING INTO DYSFUNCTIONAL RELATIONSHIP OF RHETT & SCARLETT] Both the book and movie are criticized to varying degrees for the depiction of black people both as slaves and freed men and women.

Of note is how Rhett Butler engages in misogeny and possibly marital rape. In one scene, it is unclear to the viewer if consent was given (offscreen) by Scarlett O’Hara or not. For decades, this was interpreted as an epic romance rather than romanticized and unhealthy relationship dynamics.

Going back 80+ years, starring Clark Gable and Vivian Leigh as the title characters depict what, to the eyes of viewers in the 2020’s, are romanticized, unhealthy relationship dynamics.

The Quiet Man

A passion project for almost 20 years, John Ford won his fourth Best Director Academy Award for this 1952 movie (still the record for most best director Oscars) starring John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara. Based on a 1933 Saturday Evening Post short story by Irish novelist Maurice Walsh, the film not only features a colorful cast of characters, but also offers vivid, lush imagery and sweeping views of the Irish landscape befitting the talents of Winton C. Hoch and Archie Stout who won Oscars for Best Cinematography.

The Quiet Man is a beloved movie that for many families is a St. Patrick’s Day tradition. It presents an idyllic, romantic vision of rural Ireland during the Irish Free State era of the 1920’s and is something of an Irish fairy tale.

As charming as it may be, it is not without criticisms. Gillespie notes that the characters are Irish stereotypes “alternatively appear as quaint in their customs, charming in their belligerence, and unreformable in their alcoholic sloth” adding that “an insistent image of destructiveness emerges. Despite Barry Fitzgerald’s Stage Irish portrayal of the amiable alcoholic, Michaeleen O’Flynn, The Quiet Man insistently portrays the dehumanizing effects of liquor by making characters look foolish (Michaeleen), pugnacious (Danaher), or abusive (Thornton).”(Gillespie, 2002)

“Throughout the film, violence surfaces as the immediate, abusive response of the strong to the weak.”

TOXIC MASCULINITY. "dated gender stereotypes" and "trivialization of domestic violence" The much larger husband uses physical force to express to his wife that he’s unhappy with her by dragging her across the Irish countryside.

Violence of Irish men getting drunk at every opportunity and representatives of the Catholic Church intrusively interfering in parishoners private lives.

Gillespie describes the film as “pronounced discomfort at what they saw as patronizing and stereotypical renditions of the Irish culture and character, which infantilizes and oversimplifies the rhythm and routines of Irish life.” Adding that “ the Irish people alternatively appear as quaint in their customs, charming in their belligerence, and unreformable in their alcoholic sloth.” (Gillespie, 2002)

“The film gives ample evidence of Mary Kate s fierce independence, of her indomitable nature, and of her nearly ungovernable temperament.”

“On the surface, the film depicts alcohol as little more than a harmless salve facilitating social exchanges. Nonetheless, on closer examination, an insistent image of destructiveness emerges. Despite Barry Fitzgerald's Stage Irish portrayal of the amiable alcoholic, Michaeleen O'Flynn, The Quiet Man insistently portrays the dehumanizing effects of liquor by making characters look foolish (Michaeleen), pugnacious (Danaher), or abusive (Thornton).”

With regards to the treatment of women, [KISS AT THE DOOR]

Gillespie, Michael Patrick. “The Myth of Hidden Ireland: The Corrosive Effect of Place in ‘The Quiet Man.’” New Hibernia Review / Iris Éireannach Nua, vol. 6, no. 1, 2002, pp. 18–32. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20646356. Accessed 1 Jan. 2025.

The Notebook (2004)

More recently, this popular movie depicts Ryan Gosling’s character threatens self-harm (jumping off a ferris wheel) in order to manipulate Amy Adam’s character to do what he wants.

The Notebook. (2004) Ryan Gosling’s character threatens self-harm to manipulate her character to do what he wants.

13 Reasons Why (2017)

This Netflix series offered a romanticized depiction of teen suicide that was problematic for a number of reasons.

The romantic fairy tale stories of the Disney princesses offer interesting interpretations when viewed with a critical eye. Questions arise as to whether the imagery and examples provided by the various Disney princesses adversely influence the behavior, body esteem, and prosocial behavior of young children both girls and boys.

Focus on Disney princesses generates interest because the primary target market are young girls. Since early childhood is when General criticisms of the Disney princesses include often defined by their appearance, are concerned with finding love, and are often rescued by men. [SOURCE?] Children raised on Disney princess movies are repeatedly offered messages about relationship dynamics that, again, are questionable to a 2020’s-era audience.

Bruce suggests that the Disney princess example presents false expectations of womanhood as the first three generations of princesses take little action and rely on their own beauty in pursuing their primary objective of finding and marrying her “Prince Charming”. (Bruce, 2007; Reilly, 2016)

Big Business

Although Snow White, the first Disney princess, was introduced in 1937, The Walt Disney Company (WDC) did not create the Disney Princess Line as a distinct media and merchandise brand until 2000. The original members were the “Classic” princesses (Snow White, Cinderella, and Aurora aka Sleeping Beauty), the “Renaissance” princesses Ariel, Belle, and Jasmine from The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), and Aladdin (1992), respectively.

Although not princesses, four other characters were included in this first group: Esmerelda from The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1994), Pocahontas from Pocahontas (1995), Mulan from Mulan (1998), and Tinker Bell. Esmeralda and Tinker Bell were later removed (Tinker Bell being moved to the Fairy Line)

Beginning in 2010, the “Modern” princesses were subsequently added: Tiana, Rapunzel, Merida, Moana, and Raya from The Princess and the Frog (2009), Tangled (2010), Brave (2013), Moana (2016), and Raya and the Last Dragon (2021), respectively.

This current group does not include all Disney princesses or special case characters . Other characters that were considered but never officially added to the line for various reasons are Jane Porter (Tarzan), Giselle (Enchanted), and Anna and Elsa (Frozen). Jane perhaps was not included because her character look was too similar to Belle. Giselle would have required image rights to use Amy Adam’s likeness. And, Anna and Else are part of the lucrative Frozen brand and require no additional marketing.

In addition to movies and toys, WDC extensively licensed the princess images on merchandise from books, clothes (including tiaras), home decor, comforters, and sheets to beauty products to band aids and more. It is one of the most popular brands of movies and merchandising in the world based on revenue. Sales from princess products provide a significant contribution to WDC’s bottom line. Revenue has grown from about $300 million in 2000 to $3 billion in 2012 to $4.5 billion in 2023. (Bruce, 2007; Coyne, 2016; Other, 2024)

In 2024, WDC announced “Create Your World”, a multi-year marketing campaign featuring the princesses. WDC states that the campaign includes “theatrical and streaming content, Disney Parks experiences, new music cover releases, consumer products, and more to encourage fans of all ages, everywhere, to discover their own brand of Princess magic that lies within them.”

WDC points out that “for generations, Disney Princesses have inspired women and girls to be true to their heart, dig a little deeper, and see how far they’ll go.” (“Disney Princesses Come Together to Inspire Girls to “Create Your Worldâ€� Through New Multi-Year Brand Campaign”, July 31, 2024 Source: Source

Given the success of the Disney Princess Line, a many children, both boys and girls, view the movies and merchandise and literally spend years with the princesses and are exposed to the messaging inherent in these movies and explicit in their marketing.

What they represent

Reilly groups the Disney princesses into four distinct groups that he names Generations 1 thru 4:

Criticisms

“Disney likes to think of the Princesses as role models, but what a sorry bunch of wusses they are. Typically, they spend much of their time in captivity or a coma, waking up only when a Prince comes along and kisses them. The most striking exception is Mulan, who dresses as a boy to fight in the army, but–like the other Princess of color, Pocahontas–she lacks full Princess status and does not warrant a line of tiaras and gowns. Otherwise the Princesses have no ambitions and no marketable skills, although both Snow White and Cinderella are good at housecleaning.” (Ehrenreich, 2007)

Orenstein, Peggy. “What’s Wrong With Cinderella?rdquo; The New York Times Magazine. December 24, 2006.

Ehrenreich, Barbara. “Bonfire of the Disney Princesses.” The Nation. December 24, 2007. Access January 01, 2025.

Negative impact on body image and stereotype of skinny is good.

REILLY, C. (2016). “CHAPTER FOUR: An Encouraging Evolution Among the Disney Princesses? A Critical Feminist Analysis”. Counterpoints: Teaching With Disney, 477, 51–63.

Source: Source

Media & Violence

Anderson, C. A., Berkowitz, L., Donnerstein, E., Huesmann, L. R., Johnson, J. D., Linz, D., Malamuth, N. M., & Wartella, E. (2003). “The Influence of Media Violence on Youth”. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4(3), 81–110.

Other examples of cinematic portrayals of unhealthy relationships include:

13 Reasons Why. A romanticized depiction of suicide.

Adolescents have no idea of healthy relationships and how to be clear and assertive in defining boundaries. “These media stereotypes lead audiences ‘to believe that unhealthy power dynamics are okay,’ Lee says. And it gives them ‘a false sense of reality’ that healthy relationships don’t exist in real life.”

Rutherford, A., & Baker, S. (2021). “The Disney ‘Princess Bubble’ as a Cultural Influencer.” M/C Journal, 24(1). https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.2742 (Original work published March 13, 2021)

Understanding the different forms of teen dating violence

by Maya Pottiger

December 1, 2023

What is the connection between Media, Sexual Violence, and Systems of Oppression?

March 08, 202

I Survived Teen Dating Violence. Here’s How We Can Prevent It

By Angela Kim • May 3, 2022

California Health Report

“Teaching children about intimate partner violence isn’t only the job of schools. I encourage parents, guardians and even older siblings to talk with children about boundaries and how to articulate these clearly and assertively. For older teenagers, this might involve discussing their power to define their own boundaries around sex and intimacy. Addressing the broader societal problem of domestic violence requires policy and funding changes. But if you want to take action on this issue yourself, begin having conversations about healthy and unhealthy relationships with the children in your life.”

Sources: Kim; Pottiger

Video Games & Violence

Anderson, 2003

“There is insufficient scientific evidence to support a causal link between violent video games and violent behavior” 2020 resolution adopted by the American Psychological Association.

United States Supreme Court

Brown v. EMA

Source: source

&lduo;The State’s evidence is not compelling. California relies primarily on the research of Dr. Craig Anderson and a few other research psychologists whose studies purport to show a connection between exposure to violent video games and harmful effects on children. These studies have been rejected by every court to consider them,6 and with good reason: They do not prove that violent video games cause minors to act aggressively (which would at least be a beginning). Instead, ‘[n]early all of the research is based on correlation, not evidence of causation, and most of the studies suffer from significant, admitted flaws in methodology.&rsqou; 556 F. 3d, at 964. They show at best some correlation between exposure to violent entertainment and minuscule real-world effects, such as children’s feeling more aggressive or making louder noises in the few minutes after playing a violent game than after playing a nonviolent game.”

Cunningham, S., Engelstätter, B., & Ward, M. R. (2016). “Violent Video Games and Violent Crime.” Southern Economic Journal, 82(4), 1247–1265. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26632315

Ferguson, C. J. (2014). “Violent Video Games, Mass Shootings, and the Supreme Court: Lessons for the Legal Community in the Wake of Recent Free Speech Cases and Mass Shootings.” New Criminal Law Review: An International and Interdisciplinary Journal, 17(4), 553–586. https://doi.org/10.1525/nclr.2014.17.4.553

Ward, M. R. (2010). “Video Games and Adolescent Fighting.” The Journal of Law & Economics, 53(3), 611–628. https://doi.org/10.1086/605509

Movie sexual exposure (MSE) is also shown to have an effect on the sexual behavior of adolescents affecting the age of sexual debut and subsequent sexual risk taking. Early sexual debut is associated with increased number of sexual partners, inconsistent condom use, and increased risk of sexually transmitted infections (STI’s). (O’Hara et al., 2012)

Youth are exposed to a high degree of sex in movies that is portrayed in an unrealistic and/or risk-promoting manner. In movies from 1983 to 2003, 70% of sexaction were between newly aquainted parnters; 98% - no reference to contraception; 89% - no consequences. Only “9% of sexual content in movies contined messages promoting sexual health.”

How: “Wright (2011) posited that the effect of media on sexual behavior is driven by the acquisition and activation of sexual scripts. Scripts provide behavioral options in social situations, including those that may lead to sexual behavior, and the content of scripts is often influenced by media.” (O’Hara et al., 2012)

O’Hara, Ross E., et al. “Greater Exposure to Sexual Content in Popular Movies Predicts Earlier Sexual Debut and Increased Sexual Risk Taking.” Psychological Science, vol. 23, no. 9, 2012, pp. 984–93.

JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23260357. Accessed 19 Dec. 2024.

MANGANELLO, JENNIFER A. “TEENS, DATING VIOLENCE, AND MEDIA USE: A Review of the Literature and Conceptual Model for Future Research.” Trauma, Violence & Abuse, vol. 9, no. 1, 2008, pp. 3–18.

JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26636172. Accessed 18 Dec. 2024.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/26636172

SOCIAL MEDIA

“Overall, it is important to emphasize that social media’s association with mental health problems is not straightforward or causally linked. Nevertheless, when considering the vulnerability of adolescents to these types of algorithmic priming, we need to consider their unique susceptibilities. In particular, unlike the adult brain, the adolescent brain is not fully developed, and thus is more susceptible to manipulation.” (Bradshaw, 2024)

Bradshaw, Samantha, and Tracy Vaillancourt. “Freedom of Thought, Social Media and the Teen Brain.’ Centre for International Governance Innovation, 2024.

JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep57753. Accessed 20 Dec. 2024.

Beach Method: a comprehensive procedure for media content coding.

Sensation Seeking: the tendency to seek novel and intense stimulation (Arnett, 1994)

Definition: “Like adult domestic violence, teen dating violence is a pattern of controlling behavior, in which one partner attempts to assert their power through physical, emotional, verbal, psychological, and sexual abuse. This will often be coupled by instances of jealousy, coercion, manipulation, possessiveness and an overall threatening demeanor, many times increasing in severity as the relationship continues. Dating violence can affect people from all socioeconomic, racial, ethnic, and religious backgrounds, and occurs in heterosexual, gay, and lesbian relationships.”

Domestic Violence Action Center

https://domesticviolenceactioncenter.org/what-about-teen-dating-violence/

Trauma informed Teen Dating Violence Prevention

“This webinar explores strategies to developing a youth-friendly trauma-informed program, a deeper exploration of how trauma, family violence, and community violence contribute to Teen Dating Violence.”

Download File

Download other file

Rodenhizer, Kara Anne E., and Katie M. Edwards. “The Impacts of Sexual Media Exposure on Adolescent and Emerging Adults’ Dating and Sexual Violence Attitudes and Behaviors: A Critical Review of the Literature.” Trauma, Violence & Abuse, vol. 20, no. 4, 2019, pp. 439–52. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/27010980. Accessed 17 Dec. 2024.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS). National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars

Suicide was second leading cause of death for adolescents ages 10- to 17-years-old for the 5-year period 2018-2022.

Bridge JA, Greenhouse JB, Ruch D, Stevens J, Ackerman J, Sheftall AH, Horowitz LM, Kelleher KJ, Campo JV. “Association Between the Release of Netflix’s 13 Reasons Why and Suicide Rates in the United States: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis.” J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020 Feb;59(2):236-243. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.04.020. Epub 2019 Apr 28. PMID: 31042568; PMCID: PMC6817407.

Source: Source

"This national study identified an increase in suicide rates for children and adolescents aged 10 to 17 years after the release of the first season of the Netflix series 13 Reasons Why. We estimate that the series’ release was associated with approximately 195 additional suicide deaths in 2017 for 10- to 17-year-olds."

Romer D. Reanalysis of the Bridge et al. study of suicide following release of 13 Reasons Why. PLoS One. 2020 Jan 16;15(1):e0227545. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227545. PMID: 31945088; PMCID: PMC6964826.

Source: Source

“This analysis suggests that it is difficult to attribute the rise in male suicide in April 2017 to the show, especially considering that males were not the audience at risk of contagion. Furthermore, the increase in April was not different from the increase that occurred in March before the show was released, again suggesting that other factors were at play in those two months. Finally, Bridge et al. attributed elevations in suicide much past the month of the show’s release, but these changes were more likely attributable to the large increase in suicide observed in boys for the year of 2017, a trend that had started in 2008. Thus, it is equally if not more likely that the rise in those two months was attributable to other sources that were responsible for the large increase in 2017.”

Bridge JA, Greenhouse JB, Kelleher KJ, Campo JV. Formal Comment: Romer study fails at following core principles of reanalysis. PLoS One. 2020 Nov 18;15(11):e0237184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237184. PMID: 33206659; PMCID: PMC7673571.

Source: Source

Counter to Romer’s Reanalysis of Bridge’s, et al. 2019 study. In addition to questioning findings of Romer's reanalysis, Bridge points out that Romer actually supports Bridge's findings: suicides of boys significantly increased in April 2017 while suicides of girls did not show a statistical change.

“Romer’s tendency to minimize the observed increase in suicide in April 2017 fails to consider the potential impact of ‘binge watching’ of the series in its first month of release, also discussed in our paper.”

"The Romer study fails at following other core principles of reanalysis...Romer [1] also fails to articulate clearly that ours was one of two independently researched papers [2, 7] published in peer-reviewed journals that found an increase in youth suicide rates associated with the release of 13RW. In the Niederkrotenthaler et al. [7] paper, the authors extended the pediatric age range to 19 years and found a significant association between the release of 13RW and suicide in both boys and girls."

National Recommendations for Depicting Suicide. Available at: The National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention

“No matter how much you try to defend a graphic portrayal of suicide to raise awareness, there is no way it will change the very real and dangerous suicide risk among the population that is vulnerable,” she said. “It’s very tempting to use that kind of graphic portrayal, thinking you won’t be able to drive your point home if you don’t, but it’s a harmful message.&dquo;

- Christine Moutier, chief medical officer of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP)

How to Talk with Your Teen about “13 Reasons Why”

May 05, 2017

https://sprc.org/news/how-to-talk-with-your-teen-about-13-reasons-why/

Wang H, Yue Z, S D. Challenges with using popular entertainment to address mental health: a content analysis of Netflix series 13 Reasons Why controversy in mainstream news coverage. Front Psychiatry. 2023 Aug 30;14:1214822. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1214822. PMID: 37711419; PMCID: PMC10498920.

Source: Source

1. Media Stereotypes tend to be selective and biased; May stigmatize suicidal individuals and suppress the intention to seek professional help.

2. Copycat behavior especially w/ celebrity suicides.

Show: suicide contagion (triggering); Glamorized risky behaviors including suicide: exacting revenge; Portrayal of adults as incompetent and uncaring.

RESULTS: Criticism: 20.1% / 61.6%; Praise 2.0%; 6.0%

1 in 3 articles included mental health resources.

Wang H, Parris JJ (2021) Popular media as a double-edged sword: An entertainment narrative analysis of the controversial Netflix series 13 Reasons Why. PLoS ONE 16(8): e0255610. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255610

Source: Source

teen suicide and related issues of depression, bullying; substance abuse; and sexual assault.

Niederkrotenthaler T, Stack S, Till B, et al. Association of Increased Youth Suicides in the United States With the Release of 13 Reasons Why. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(9):933–940. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0922

Increase in suicide rates for adolescents ages 10-19 especially for girls. No corresponding increase in suicide numbers for other age groups. This increase corresponds to the max interest in 13RW from its premier in April 2017 to June 2017 when interest became negligible as evidenced on Twitter, etc.

https://www.bphope.com/bipolar-buzz/8-honest-reactions-to-13-reasons-why/

“In a research paper published by Dr. Michael B. Pitt and colleagues in Pediatrics, it advises that at-risk patients abstain from watching the show’s ‘graphically glorified’ version of suicide. Although Dr. Pitt and colleagues agree that a dialogue about mental health dialogue is vital, they maintain ‘13 Reasons Why’ violates established best practices surrounding portrayals of suicide in the media.”

Florian Arendt, Sebastian Scherr, Josh Pasek, Patrick E. Jamieson, Daniel Romer,

Investigating harmful and helpful effects of watching season 2 of 13 Reasons Why: Results of a two-wave U.S. panel survey,

Social Science & Medicine,

Volume 232,

2019,

Pages 489-498,

ISSN 0277-9536,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.04.007.

Source: Source

“The results suggest that a fictional story with a focus on suicidal content can have both harmful and helpful effects.”

THE HARVARD POLITICAL REVIEW

https://harvardpolitics.com/a-poorly-taped-show-mental-health-in-13-reasons-why/

“The show is, at its most basic, a glamorized revenge fantasy. Unlike a suicide in real life, Hannah Baker continues to find herself present after her death, played out in the imaginations of the show’s other characters, seeing her ploy for revenge transpire. She gets a twisted feeling of justice she couldn’t see come to fruition while alive. Such a portrayal romanticizes suicide rather than educating viewers or fostering conversations about it. Unintentionally, the writers of the show perpetuate the narrative that Hannah’s death solved her problems; it illustrated that suicide was an adequate way of getting the attention and care she didn’t previously receive from her friends and school’s administration.”

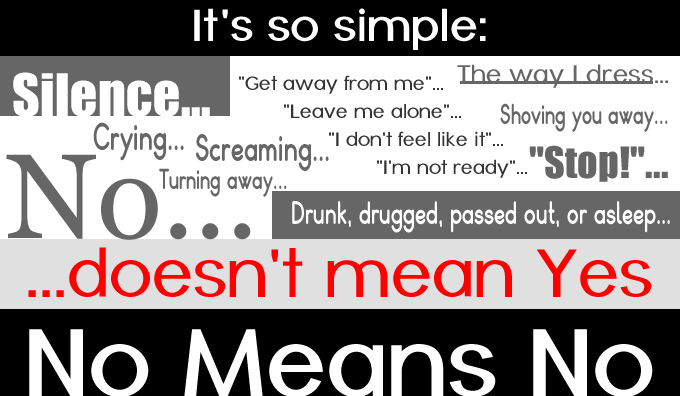

The simple explanation is, “If it’s not yes, it’s no.”

Consent is about taking an active, fully aware role in the decision-making process and giving a clear, definitive "Yes". A more involved definition is that consent is the positive cooperation in act or attitude pursuant to an exercise of free will. A person must act freely and voluntarily and have knowledge of the act or transaction involved.

Sexual assault is physical contact of a sexual nature in the absence of clear, knowing and voluntary consent.

Very Important: An individual cannot consent:

who is unaware that the act is being committed;

who is obviously incapacitated by any drug or intoxicant;

who is coerced by supervisory or disciplinary authority;

who is being purposely compelled by force, threat of force, or deception;

whose ability to consent or resist is obviously impaired because of mental or physical condition.

Only a person who willingly says “Yes” without threats, fear, or being drunk/drugged and who is fully aware and completely understands what is being asked of them and has complete freedom of choice in the matter is giving their consent.

A person that is drunk or drugged — even if the word “yes” is spoken — cannot give their consent. Likewise, a person that says, "No", or doesn’t say anything at all — such as an unconscious person — has not given their consent.That’s right: No answer or no response does not mean and is not actually a “Yes.”

Just because someone said “Yes” once doesn’t mean there is an open invitation, automatic green light to the same question at any time in the future. Consent must be given every time — in words and actions — to a clear question. Maybe it’s a one time deal. Maybe for two or three times and that’s it. It depends on the person, in the moment.

AND, THIS IS THE IMPORTANT PART. Watch this brilliant video to better understand consent. It's an effective use of stick figures and a cup of tea entitled, “How to Explain Consensual Sex with a Cup of Tea.”

WARNING: There are two versions of this video. One is Clean and the other is Explicit. The Explicit version uses extremely strong language to get the point across.

Copyright ©2015 Emmeline May and Blue Seat Studios

"Clean" version

"Explicit" version: very strong language

Söchting (p83) identifies several proximal risk factors have been examined in relation to rape vulnerability including:

alcohol use

dating location

attitudes and beliefs

behavior & frequency

ability to detect danger cues

assertiveness and communication

Prior victimization also appears to be a very strong risk factor as women with multiple incidents of victimization seem to have difficulty in detecting dangerous situations (Söchting: 86).

Four risk factors are particularly relevant to college students:

alcohol

familiarity

date rape drugs

location (including the victim’s home and car)

According to the United States Department of Justice, sexual assault is a vastly underreported crime. The FBI Uniform Crime Report 2000 states that a rape is reported about once every five minutes (911rape.org), whereas the Rape, Assault, & Incest National Network (RAINN), using data from the USDOJ, calculates that an average of one sexual assault occurs every 2.5 minutes. Additionally, one in six American women are victims of sexual assault (one in 33 men), and there were an annual average of 200,780 victims of rape, attempted rape or sexual assault in 2004-05 (RAINN).

Unfortunately, sexual assault on campus follows the national trend with less than five percent of completed and attempted rapes of college students believed to be reported (Karjane: 5). A variety of individual, institutional, and socio-cultural factors at colleges and universities contribute to victims’ reluctance to report the crime. Reasons given for not reporting include not fully understanding what occurred, campus drug and alcohol use policies, adjudication, and trauma response (psychological distress, denial, etc.).

Acquaintance rape is especially troubling to the victim because of pre-existing relationship between the victim and perpetrator that result in a range of conflicting emotions that inhibit a willingness to report (Karjane: 9). Bill Foley, former Chief of Public Safety at Saint Mary’s College of California (Moraga, CA) believes that embarrassment is a key factor why sexual assault is not more widely reported.

These numbers are especially relevant to college and university students:

Break the Cycle offers a campaign entitled, Password: Consent. This is a campaign to end the Red Zone, the time that students first arrive on campus thru to Thanksgiving break. This is the time that students are most likely to be sexually assaulted than at any time in their college careers.

Teen Dating Violence: A Closer Look at Adolescent Romantic Relationships

by Carrie Mulford, Ph.D., and Peggy C. Giordano, Ph.D.

NIJ Journal, No. 261, October 2008

Source: National Institute of Justice

1 in 10 teens experience physical abuse by a romantic partner.

3 in 10 teens report verbal or psychological abuse by a romantic partner.

GIRLS v. BOYS. Girls experiencing teen dating violence are more likely than boys to suffer long-term negative behavioral and health consequences, including suicide attempts, depression, cigarette smoking and marijuana use.

SURPRISE: Equal power between sexes. This differs from traditional power imbalance of adult relationships.

Longitudinal Associations Between Teen Dating Violence Victimization and Adverse Health Outcomes

Deinera Exner-Cortens, MPH, John Eckenrode, PhD, and Emily Rothman, ScD

Pediatrics 2013; 131:71-78

Source: American Academy of Pediatrics Publications

METHOD: 5681 12- to 18-year-old adolescents who reported heterosexual dating experiences at Wave 2. These participants were followed-up ~5 years later (Wave 3) when they were aged 18 to 25.

RESULTS: Compared with participants reporting no teen dating violence victimization at Wave 2, female participants experiencing victimization reported increased heavy episodic drinking, depressive symptomatology, suicidal ideation, smoking, and IPV victimization at Wave 3, whereas male participants experiencing victimization reported increased antisocial behaviors, suicidal ideation, marijuana use, and IPV victimization at Wave 3, controlling for sociodemographics, child maltreatment, and pubertal status.

CONCLUSIONS: The results from the present analyses suggest that dating violence experienced during adolescence is related to adverse health outcomes in young adulthood. Findings from this study emphasize the importance of screening and offering secondary prevention programs to both male and female victims.

Teen Dating Violence (Physical and Sexual) Among US High School Students

Findings From the 2013 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey

Kevin J. Vagi, PhD; Emily O’Malley Olsen, MSPH; Kathleen C. Basile, PhD; et al

JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(5):474-482. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3577

Source: JAMA Pediatrics

BOTH PHYSICAL & SEXUAL TDV: Male and female students who experienced both physical and sexual TDV had a higher prevalence of every health risk behavior than students who experienced no TDV. In addition, male students that experienced both forms of TDV showed a stronger association with health-risk behaviors than female students who experienced both. Female students who experienced both forms of TDV were twice as likely to attempt suicide than students that experienced either physical or sexual TDV alone. Male students were three times as likely to attempt suicide in the same category. These findings support the findings of other studies.

SEXUAL TDV ONLY: The associations with health-risk behaviors were not consistent among students who experienced sexual TDV only:

HEALTH-RISK BEHAVIORS: seriously consider attempting suicide, make a suicide plan, attempt suicide, get in a physical fight, carry a weapon, be electronically bullied, and report current alcohol use and binge drinking, marijuana use, cocaine use, had sex with 4 or more people, currently sexually active.

The Rate of Cyber Dating Abuse among Teens and How It Relates to Other Forms of Teen Dating Violence

Janine M. Zweig, Meredith Dank, Jennifer Yahner, Pamela Lachman

Journal of Youth and Adolescence

July 2013, Volume 42, Issue 7, pp 1063-1077

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10964-013-9922-8

Urban Institute, Justice Policy Center

Source: Uban.org [PDF]

MORE THAN 25% of 3,745 teenagers in a dating relationship experienced some form of cyber dating abuse victimization in the prior year to the survey. Teenagers reported that their social networking accounts were hacked without permission, that they were texted about unwanted sex and that they were pressured to send sexual or naked photos of themselves.

Specifically, they found eight ways in which partners used electronic communications, the last six of which were related to violence, abuse, or controlling behaviors:

(1) establishing a relationship;

(2) nonaggressive communication;

(3) arguing;

(4) monitoring the whereabouts of a partner or controlling their activities;

(5) emotional aggression toward a partner;

(6) seeking help during a violent episode;

(7) distancing a partner’s access to self by not responding to calls, texts, and other contacts via technology; and

(8) reestablishing contact after a violent episode.

Nearly 6 percent of teenagers said their partners had posted embarrassing photos of them online, and 5 percent reported their partners wrote “nasty” comments about them on the partner’s profile page.

More than half reported physical abuse, which ranged from scratching to choking. One-third said they were sexually coerced, defined as being forced or pressured to perform sex acts they didn’t want to do. Four percent of teenagers said they were harmed only in digital form.

Causes and consequences of adolescent dating violence: a systematic review

by Taquette SR, Monteiro DLM

J Inj Violence Res.

2019 Jul;11(2):137-147. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v11i2.1061. Epub 2019 Jul 2. PMID: 31263089; PMCID: PMC6646825.

link

ADVERSE HEALTH EFFECTS

Long-term Adverse Outcomes Associated With Teen Dating Violence: A Systematic Review

by Piolanti A, Waller F, Schmid IE, et al.

Pediatrics.

2023;151(6):e2022059654

link

ADVERSE HEALTH EFFECTS

NEXT: Consent

An absolutely required step for intimate relationships.